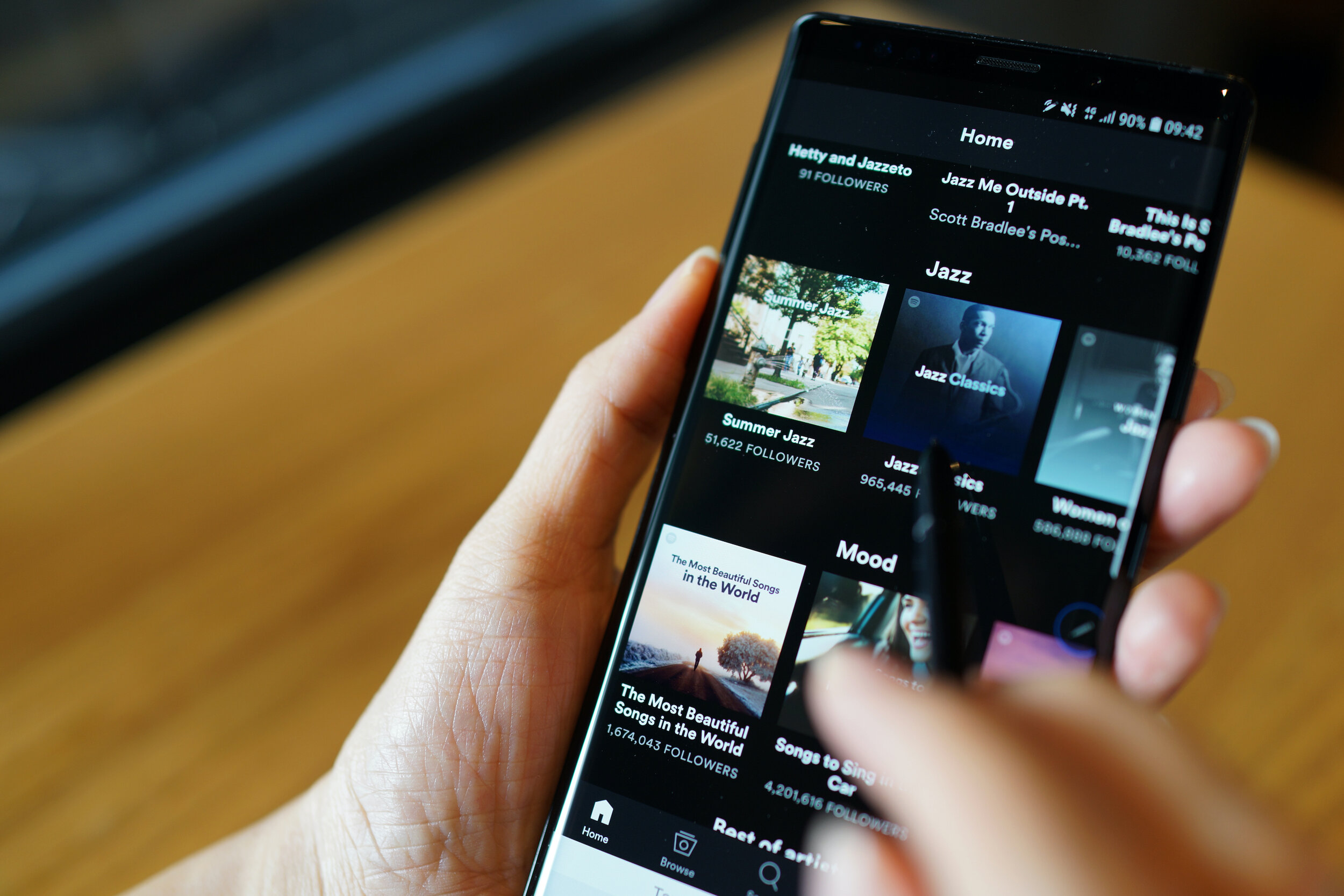

300 million active users sing the praises of Spotify—the most successful music-streaming services out there today, easily beating out comparable services from Apple, Amazon, and Google. The service now boasts some 138 million paying subscribers—double that of its closest competitor. The secret to Spotify’s success is its uncanny ability to propose personalized music recommendations through features such as its ‘Discovery Weekly’ playlist. Every Monday, Spotify users are treated to 30 new songs that they have typically never heard of but usually love. Over the past five years, Spotify users have spent more than two billion hours tuned into these personalized playlists, discovering new music they adore, and growing ever-more-loyal to the platform as a result.

This got me thinking — “What is it exactly that Spotify does to make personalized discovery so successful? And what would it take for an online grocer to “replicate this success?”

At least part of the answer comes in how Spotify thinks about music. Since 2014 the service has owned The Echo Nest, a spinout from the MIT Media Lab that creates personalized music taste profiles based on the listening patterns of each user. But rather than using only broad heuristic approaches like musical genres, Spotify breaks each song you listen to down into over fifteen detailed aural characteristics ranging from basic descriptors like musical key, time signature, and volume to far more esoteric conditions, including “speechiness,” “positiveness,” and “danceability.” In other words, the Spotify personalization algorithm cares as much (or more) about the detailed “ingredients,”“texture,” and “flavor” of a song as it cares about the broad category that the song lives in.

You can probably see where I’m going with this. But before we get there, let’s take a look at how things might pan out if Spotify did it a different way. Let’s say I listened to the Norah Jones’ song Come Away with Me. A simple analysis might show that this is a jazz song, or what some might call “easy listening.” It would be a fair guess that I might like to hear more tunes from Norah Jones and other artists in her genre. But one of the most popular jazz/easy listening artists of all time is Kenny G, and–with apologies to Kenny G fans– I don’t want to hear that. If the algorithm was a little smarter (it is, by the way), it would know that Norah Jones is a female vocalist with relatively young, pop sensibilities, while Kenny G is an instrumentalist whose core fan base is at least two to three times my age. The algorithm would do far better recommending Billie Eilish, Amy Winehouse, or even Lady Gaga.

In truth, I tend to prefer electronic music, and what really gets me going is a great drumline. Whether it’s indie, house, or even modern R&B, I’ll take a fast and funky rhythm pattern over a killer bass line any day of the week. Spotify knows this about me. They dig deep into the alchemy of the songs I stream and manage to distill out the essential elements that make my personal tastes unique to me. The algorithm is smart enough to know that I might like a particular song by an artist because of the instrumentation, tempo, lyrics, or melodic style without really being a fan. That’s why my Spotify recommendations often contain suggestions of music from artists and genres outside of what I normally stream. And sure enough, most of the recommended songs have something about them which makes me feel they’re “my” kind of music!

So how might this work for grocery? Just like a song is defined by numerous characteristics, so too is a food product: There is its broad food group, such as protein, vegetable, dairy, or grain; its subgroup, such as beef, chicken, or fish; it’s ontology as a main ingredient, side dish, or sauce; its country of origin; whether it is fresh or packaged; whether it is a versatile, stand-alone recipe item or a convenient, pret-a-manger meal; its caloric count and nutritional content; and more esoteric considerations such as whether it is gluten-free, vegan, or hallal. Food items can also be thought of in terms of recipes and what other items the product is typically paired with—such as the relationship between bread, peanut butter, and jam, or that between pasta, mozzarella, and tomato sauce. There are flavor profiles such as sweet, salty, spicy, or umami. There is the brand, whether the item is frozen, canned, or bottled. The complete range of characteristics for any one food item is just incredibly robust.

Brands are parallel to songwriters, and food products are like songs. Rhythm, instrumentation, and melody are homologous to texture, ingredients, and flavor. With the right algorithmic approach, you can tease out a dozen or more taste affinities from food that resemble the musical affinities I talked about earlier. That will allow you to help shoppers discover new food products that truly appeal to them, rather than using only generic heuristics. Instead of “customers who bought X also tried Y,” you can use “since you are a vegan customer who frequently buys spicy foods that are easy to make, we thought you might like to try this dairy-free pepper jack cheese and soy-based, organic, taco filling. By the way, since you have purchased light, imported beers in the past, you might want to try this new Sol Limon y Sal beer to go with that!”

Personalized recommendations like these create a 5% or greater basket uplift. They also replicate online the joy of food discovery that customers experience in-store. With the brick-and-mortar experience, colorful endcap displays, dump bins, and aisles of exciting choices appeal to the “gathering” aspect of our hunter-gatherer evolution. It’s enjoyable and even slightly addictive. Online and in mobile shopping apps, the “Spotify approach” can empower grocers to replicate that joyful discovery process by presenting the most attractive options to customers within the very limited space available. That goes well beyond lifting basket size. By delivering an incredible user experience to shoppers, effective personalization also increases loyalty, shopping frequency, and net promoter score.

And that—with a tip of the hat to Spotify—should be music to grocers’ ears.